(Reindorf, Carl Christian. History of the Gold Coast and Asante. 2nd Edition. Ghana University Press, 2007) A thematic review by Gyau Kumi Adu Email: (joewykay55@gmail.com)

Have you ever thought why “history” is the mother of all knowledge? One reason is that it shows the level of progress of any body of knowledge or event, and the functions of a thing: whether it has been able to stay on course or stray off-course.

Reindorf puts it so beautifully, “A history is the methodical narration of events in the order in which they successively occurred exhibiting the origin and progress, the causes and effects, and the auxiliaries and tendencies of that which has occurred in connection with a nation. It is, as it were, the speculum and measure-tape of that nation, showing its true shape and stature. Hence a nation not possessing a history has no true representation of all the stages of its development, whether it is in a state of progress or in a state of retrogression.” Reindorf’s work is precisely that. That is, to show a true reflection of the state of affairs in Ghana, then Gold Coast, from the period 1500 to 1860, based on traditions and historical facts available during his day. Whether Ghana progressed during this period as a whole or not is left in the hand of the reader to decide. (By Gold Coast he refers to the southern states such as the Gas, Fantes, Anlos, Akuapem, Akwamu, and Akyem). However, he gives more attention to the Gas and Asantes. In the first place, writings of other ethnic groups were difficult to come across. Having in mind that Reindorf was a Ga, this book was supposed to be an initial work which shall be continued by people of other Ghanaian tribes.

The book covers a very wide scope such as tribal and inter-tribal politics and wars, economics, religious institutions, migration, social customs, agriculture and missionary work in the Gold Coast. In my opinion, Reindorf must be put on par with writers who wrote chronological accounts of their country such as Josephus – the Jewish Historian, and Tacitus – the Roman Historian, because of the quality and import of his writing.

I shall touch on the following themes in the book, blending it with some contemporary views:

- Migration and Settlement of Ghanaian Tribes (with particular interest to the Ga)

- Forms of Governments – “Fetishocracy” and “Monarchy”

- A Missionary Challenge of the Time, and its Sacrifice

- Migration and Settlement of Ghanaian Tribes (with particular interest to the Ga)

Reindorf notes that Africa obtained its name from an ancient Punic word which means “ears of corn” (pp 1). Probably this is due to how the plant has flourished in Africa for so many centuries. Ancient Egyptian agriculture was very familiar with this crop. West Africa during those times was called “Guinea” due to the territory that the ancient Guinea empire covered. Ghana particularly was situated in Upper Guinea (pp 2). The Guinean kingdom eventually decreased in power so could not oversee their vast land.

It was around this same time that the Ga people, the first to move into that region, moved from Benin to Ghana by the leadership of King Ayi Kushi, the Cushite (pp. 4). Mensah has recently made an interesting remark which supports this assertion.

They [i.e. the Ga from oral tradition] believe they are descendants of ‘CUSH’ or perhaps, Gad and Dan from the twelfth tribe of Israel. It’s fascinating to note the name of their King who led them to Ayawaso in Ghana is Ayi Kushi (Cush), and this lends support to their claim that they are Jews… It will appear that the letter “d” became omitted from the word Gad over several centuries. What we now refer to as Ga people is rather GAD people or people from the tribe of Gad. (Mensah 8-9).

Nobody discussing the origin of the Gas by-passes some of the debates that have encircled around it. Some are of the opinion that the origin of the Gas is traced to ancient societies such as the Phoenicians, Hamites, Cushites, and Jews. The leading proponent of this view is a Ga lawyer named A.B. Quartey-Papafio. Papafio asserts that the Ga came from North Africa with a mixed multitude of ‘red-skinned’ people who happened to be the Phoenicians and Cutheans. This multitude evolved into the Takye dynasty amongst the Gas. Nonetheless, neither are there records which support such an assertion nor does any oral tradition have a ‘red-skinned’ theory. (Addo, 26)

According to Ammah, probably the Ga met with the Jews in Sudan or somewhere in North Africa. The linguistic link that connects such a thought is that the Ga language is believed by some scholars to be of Sudanese origin (Azu, 8). Ammah established that the Ga ancestry can be traced to the Hamites and Cushites ethnic group, who were influenced by the Jews in the upper colony of Egypt. To further advance this position, the writer stated the similarities between the Jewish culture and the Ga culture. For example, both the Ga and Israelites circumcise their male children on the eighth day (Quartey, 60). Again, both Jews and Gas count the year according to the lunar calendar of 12 months (Quartey, 60). The Ga writer, Hubert Abbey shares this same view that the Gas originated from Israel (Abbey, 5). Nevertheless, Addo, a Ga researcher asserts that neither do these similarities tell us exactly where the Gas originated from nor are there historical documents to fill up the missing link.

Although their place of origin is an unsettled matter their place of residence is not. They moved in groups and they settled on the land bordered by the Awutu on the West (Guan speaking people), and the Adangbe on the East (Adotei, 34). The Ga people occupy a territory which extends from the Gulf of Guinea in the south to the feet of the Akuapim Hills. They have six traditional states which constitute modern-day Accra (Odotei, 61). These comprise the inhabitants of Ga Mashie (Central Accra) who are believed to be the first to settle in Ghana, Osu (Christiansborg), La (Labadi), Teshie, Nungua and Tema (Mahama, vii).

After that followed some of the Coastal tribes such as the Fantes who were the masters of the sea, the Asantes, from somewhere Central Africa, the Akyems and the Anlos of Ewe-land.

- Forms of Governance, its effect, and the place of European Missionaries.

In chapter 8, Reindorf explains there were two forms of government.

“Fetishocracy”

The word “fetish” comes from the word “fetico” which has to do with the use of magical objects and the word “cracy” from its origin means to rule. This will literally mean the rule of magical objects. However, this is problematic since the use of magical objects to represent spirits which abided to them is very foreign to the Ga. A safer translation will mean the rule of the spirit powers.

In this rule “the supreme power was formerly directly… lodged in the hands of… foretelling priests.” (114) As Reindorf notes, these priests are distinct from the normal priest who receive their office by birth (hereditary). However, these are by the election of a god from whatever tribe it willed (Ga word: wͻŋ). These priests were higher than the ordinary priests. It is believed that they were the ones that led the Gas to their above. In matters of governance, their voices carried a lot of weight in the administration of affairs. Reindorf notes that the Ewes of Anlo also used this system of governance. It was not until the time when European way of life gained ascendency that allowed the Ga chiefs to hold more power than the priests. Field states that “… after the coming of Europeans and for purposes of warfare, alliances, and negotiations with foreigners… it became necessary for the high priest to relegate much of the secular part of his duty to… maŋtsɛ (chief) and maŋkralo (town-guardian).” (3)

In this 21st century, a lot has changed in local governance. Most power is given to secular authority (the president and his cabinet) to govern the state of affairs than the traditional authority. Hence, some of these powers of the local priests are not felt as they used to. For instance, in the ancient times, the Ga priests controlled lands- they had oversight of all the Ga lands. Now it is not so.

These “foretelling priest” were prophets. Ammah points out that “The office of a prophet is not regular like a wulomo. He is not elected and installed by man; he is called, ordained, and commissioned by a power divine… The current view of the people is that the control of rain in Ga society is vested in the prophets.” (Ammah, 376 and 378) He mentions one prophet called Lomoko who made rain available at a time that the Ga lacked rain.

In a stricter sense, the Asante kingdom under Osei Tutu practiced a form of “fetishocracy” since Okomfo Anokye was more of the oracle which was contacted in all affairs by the king. He was not just a priest, but a counselor, a diviner, and one who had extraordinary magical powers. One Nungua priest, Borketey Laweh, falls in this class. He had extraordinary magical powers as well. According to tradition, he divided the sea more than once. (57-58) Laweh was responsible for giving very important predictions. For instance, he foretold the treachery that the La people had intended when they came forward to make the truce with the Nungua people. The Nungua chief will have had the upper hand, had he listened to Borketey.

Monarchy

The Asantes practised absolute monarchy in which “the king or chief had unlimited power over life and property of his subjects.” (pp. 111) Such a social organization centres on the king.

Upon the death of a king, a nephew succeeds him rather than a son. This practice, as Reindorf explains, began from the sacrifice that the sister of one Asante king, called Osei Tutu I, made. (pp 112) In those days, yam was indigenous to Takyiman. However, the king of Takyiman, Amo Yaw, had “strictly forbidden the export of it (yam) to another country.” (112) So when the Osei Tutu asked for it, he was denied the favour. Amo Yaw requested that since the plant was a noble plant unless one of them gives up a noble son (royal) for the seeds, he will not give it up. The king being in great distress entreated one of his wives to give up a son, but none offered to. Nonetheless, Osei Tutu’s sister gave up her son in exchange for that seed. Such a sacrifice made the nephews worthy of the throne. Hence, they are the ones who inherit the throne.

The king wields political and military power. In fact, the Asantes had one of the best military organizations in the country. The Asantes had courageous kings who had very well organized armies. It was so well organized that in one battle the king could order 15,000 troops to war. The introduction of the religious dimension was not originally indigenous to the Asantes. It was introduced by a powerful Awukugua priest in Akuapem called Okomfo Anokye. In one instance when the Asantes were fighting against the Dankyeras, Anokye prepared a very powerful medicine which is believed to be one of the factors that made the Asantes win that battle. (pp. 54) However, in later times, the kings disposed of the priests at will. King Osei Yaw before the battle against the Ga people got so furious and disposed of off one priest after he was told by the priest that he will be defeated.

The administration of the Asante kingdom resembled the Ancient Roman Empire in some respects. Just like the Romans, the Asantes made sure all conquered states paid allegiance to their king. This came in the form of tributes which was a way of raising money to offset the cost of war.

One main problem that emerged from this form of governance was that the way it was practised the existence of some inhumane practices. The king could behead anyone at will. This practice was not just limited to the Asante kings but other kings. Reindorf describes one Agona king who “whenever a son was born to him, ordered travelers and traders from Gomoa Asen to be waylaid and beheaded. He showed the heads to his infant child and said, ‘these are my toys, grow up and play with them.” (64) At another time, in revenge for an act committed against the Asantes, a group of people were taken to Kumasi and pounded to death in a mortar (162).

Again, during the funeral of a king or queen, three green leaves of a palm tree are cut into the form of a triangle as a necklace. Anybody that wore this necklace “is to be sacrificed to attend the deceased in the other world.” (127)

- The Missionary Challenge of the Time, and its Sacrifice

The time of Gold Coast before the coming of the Europeans was indeed a bloody era of wickedness and cruelty. Gold Coast suffered the loss of its innocent children. It was for a similar reason that Paul of the Tarsus, in meeting a culture that was deeply rooted in “dark arts” said “And the times of this ignorance God winked at; but now commandeth all men everywhere to repent: Because he hath appointed a day, in the which he will judge the world in righteousness by that man whom he hath ordained; whereof he hath given assurance unto all men, in that he hath raised him from the dead.” (Acts 17:30-31) God had to as it were, overlook all these atrocities and send European missionaries to Africa.

In my opinion, the coming of the gospel by the Europeans to Gold Coast helped to stop these practices. A counter-argument about the gospel mission in Africa is that these same missionaries were major proponents of the slave-trade. However, Africa started the practice of slavery long before the coming of the Europeans. The Europeans only made the trade more lucrative and increased it on a large scale. Again, care must be taken to distinguish between the European administration and the missionary enterprise. The first set of missionaries who came were more of chaplains to the governors and not missionaries to the indigenes. Most often, the European leaders interfered with the work of the missionaries. Just a few missionaries were sent as compared to the European merchants and soldiers. Hence they did not have much of an option to send the gospel that far but to take care of the spiritual needs of their own people.

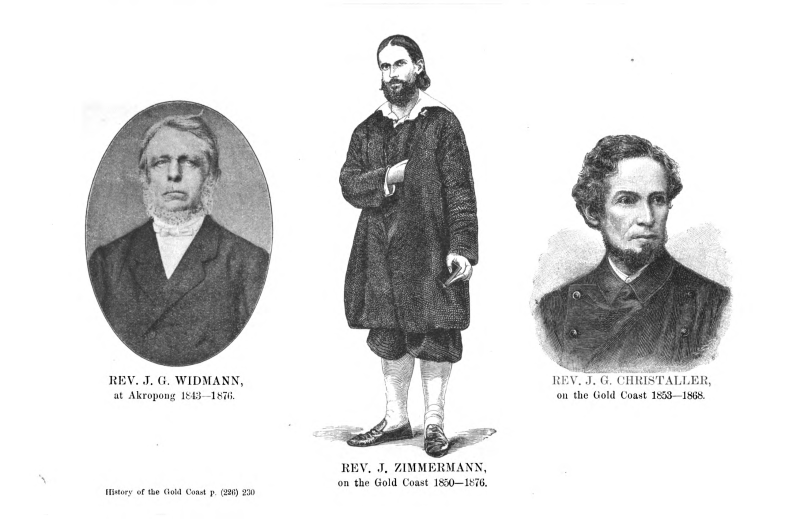

It was not until missionary societies such as the Moravian Brethren, Wesleyan Society, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), got involved with the missionary work that we saw the impact of the church to help fight these bad practices. The missionaries became the mother of the church to help birth and nurse the church of God at its infant stage. The Basel Mission, for instance, set up schools (called Salem), which they used to teach their new converts the gospel and to desist from these practices. It was a long walk to freedom. It did not take a day.

Their toils did not come without challenges. One main challenge was death. The Moravian Brethren, for instance, sent 11 people, who all died as a result of ill-health. Due to these rampant deaths “The history of the Gospel Mission in Africa is a history of the ravages of death.” (238) After the death of Rev. Dunwell, the Methodist minister, the Wesleyan Mission said: “Our greater master buries his workman, but carries on his work.” (234) As Reindorf points out, these men with some indigenous Ghanaians, used the light of the gospel to fight all these inhumane practices within the culture. Death could not stop them.

- Relevance of Carl Reindorf’s work for today.

All around the world, nation building is always tied to rich history. History gives to the nation rich experiences of the past and its ways they were addressed. Reindorf gives an interesting way in which palm wine drink (nsa) was discovered. Tradition says that there was a hunter called Ansa, who noticed an elephant pull down a palm tree and use its trunk to make holes at the base of the tree. He discovered that a liquid (palm wine) oozed out from the plant. These discoveries have to be built upon. Reindorf points out that one major problem in his time was that the discoveries made by the ancients Ghanaians were not improved. We were satisfied when we got what we will eat and drink. An example is the coral reefs discovered at the Ghana shores. No major work has been made to improve it. However, if we are not aware of the works of the ancients, how will we know what to build upon? Great strides will have been made in Ghana if we could keep the medical records of the ancients on herbal medicine.

- CONCLUSION

The book is very insightful and a must-read for anyone who wants to know the origins of our country. It paints a very detailed picture of major events in Ghana that has led to the founding of Ghana as a country.

REFERENCES

Abbey, Hubert N. Homowo in Ghana. Accra: Studio Brain Communication, 2010.

Acheampong, Twumwaa, Agyeman Boafo, Abibata Mahama, and Oti and Peprah. Preliminary Report for Ga Mashie Urban Design Lab , 2011.

Addo, Emmanuel I. K. Worldview, Way of Life and Worship: The Continuing Encounter between the Christian Faith and Ga Religion and Culture. Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum Academic, 2009.

Adu, Gyau Kumi. “The Concept of ‘Affliction’ in the Religious Context of the Indigenous Ga People of Ghana”, MPHIL Thesis. Department for the Study of Religions: University of Ghana, Legon, 2016.

Ammah, E.A. Kings, Priests, and Kinsmen: Essays on Ga culture and Society. Edited by Marion Kilson. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers, 2016.

Ammah, Charles. Ga Hɔmɔwɔ and Other Ga Adangme Festivals. Accra: Sedco Publishing Ltd, 1982.

Azu, Diana Gladys. the Ga Family and Social Changes. Cambridge: African Studies Centre, 1974.

Field, Margaret Joyce. Religion and Medicine of the Gā People Oxford University Press, 1961.

Henderson-Quartey, David K. The Ga of Ghana: History & Culture of a West African people, 2002.

Odotei, Irene. “External Influences on Ga Society and Culture.” Research Review 7, (1991): 1-2. ……… ……… “What is in a Name?: The Social and Historical Significance of Ga Names.” Research Review 5, u NS Vol 5, no. 2 (1989).